The Children's Rock Garden, Stony Creek School, Stony Creek

The teacher was Miss Elizabeth (Annie) James, who taught at the Stony Creek school between 1905 and 1913. During her tenure as head teacher she created stone rockeries whose various shapes helped educate her students in geography and geometry. But importantly, besides the usual early 20th century curriculum, she taught her students practical horticulture, the appreciation of nature, and the value of directed physical activity. The result was a garden that won a first class certificate in 1906 (the previous year the school had won a second class certificate for Annie's decoration of the school building). In 1909 Education Department Inspector Saxton claimed it 'the best school I have met'.

Ballarat Star, 21 June 1906, page 6

Who was Annie James and how did this talented teacher end up in such a backwater? In 1935, one of her students remembered her as a favourite with both boys and girls. 'She was good looking, with brown, curly hair, and always dressed in black silk' (The Age, Sat 13 Jul, 1935 Page 7). We know that she was born in 1872 in Clunes, the youngest of four daughters of Thomas James and Margaret Moynihan. She also had two brothers, one of whom, James Edwin (who, like Annie preferred to use his middle name), would go on to a successful career in New South Wales. It seems her father Thomas was a miner working in one of a number of the large mines which, in those days, dominated the skyline of Clunes.

Annie was remembered as personable and intelligent and so it was inevitable she was drawn to teaching as a career. In the late 19th century, Victoria was dotted with tiny settlements many boasting a small one-roomed school and Annie served her apprenticeship by making the rounds of these isolated communities. We know that for some years she taught at Kerrisdale State School about 17 km north west of Yea. When that school closed (a regular occurrence for such small rural schools) she was sent even further away. In 1897 she was transferred to a small school, seemingly in the middle of nowhere, between Glenrowan and Yarrawonga. This newspaper article published in the Yea Chronicle reveals she was highly regarded and, at the age of 25, had been teaching in the district for some time.

Yea Chronicle, Thursday 23 December 1897, page 3

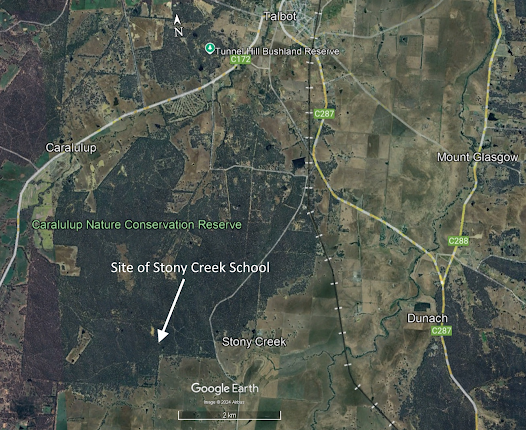

Sadly, a year later, in 1898, her father died as a result of falling down a shaft at the Iron Duke Mine in Kalgoorlie, WA (The Inquirer and Commercial News, Fri 17 Jun, 1898, Page 2). Perhaps it was for that reason she sought a teaching position closer to Clunes where her mother lived. At any rate, by 1906 she was back in the Clunes district, albeit at another small isolated rural school. Here is a photo of Annie with her class at the Stony Creek State School, some 13 km north west of Clunes. At first glance it seems odd for the Education Department to erect such a substantial brick schoolhouse far from the nearest town, within, what to our modern eyes seems rugged dry bushland (now the Caralulup Nature Conservation Reserve). But while it's a very quiet locality now, save for the occasional fossicker with a gold detector, it was once a bustling place populated by timber workers and gold miners. There was even a Eucalyptus distillery nearby. And although the school site now borders a minor dirt track, this was once the main Melbourne to Amherst Road.

Apparently, each child was given their own small rock garden to tend to. Important questions come to mind. Given the poor rocky soil, who paid for the soil and plants? Where did the copious amounts of water come from, needed to keep such a large garden alive? David Bannear, a local Central Victorian historian and archaeologist, who was instrumental in ensuring this site was added to the Victorian Heritage Database in 2015, gives a clue when he says that around this time there was a substantial movement within the Education Department to encourage creative and healthy outdoor activities at Victorian schools. Annie happened to be in the right place at the right time. Her love for horticulture meshed perfectly with these new progressive policies. As for water, the Stony Creek State School was located next to a large dam which may well have been fed by the nearby Stewarts Race- a gravity fed water channel which provided Talbot's town supply.

While a little tricky to find (head north east from the Stony Creek Picnic area), the old school site is bordered by a post and rail fence similar to the original school fence.

Finally, at the age of 41, Annie was rewarded with a posting to a large school in her home town of Clunes. Whether she went to Clunes South Primary School or the North school isn't known but we know the South school was closed in 1922 so she would have finished her teaching career at the North school, 1 Canterbury Rd, Clunes.

In 1929, her brother Edwin died at the young age of 53. He had made a very successful career as an auctioneer in New South Wales. His base was Temora but the firm of Miller and James had branches in Gilgandra and West Wyalong. His funeral was one of the largest the district had ever seen.

Upon her retirement in 1934, to mark the high esteem she was held in the community, she was given a civic reception in the Clunes Town Hall.

In 1936 she managed to visit and stay with her late brother's wife in Temora as well as visit some of the branches of her brother's auctioneering firm.

'To Live in Hearts We Leave Behind is Not to Die'. A fitting epitaph for a teacher who touched the lives of so many people and whose extraordinary rock garden at Stony Creek survives to this day.

Comments

Post a Comment